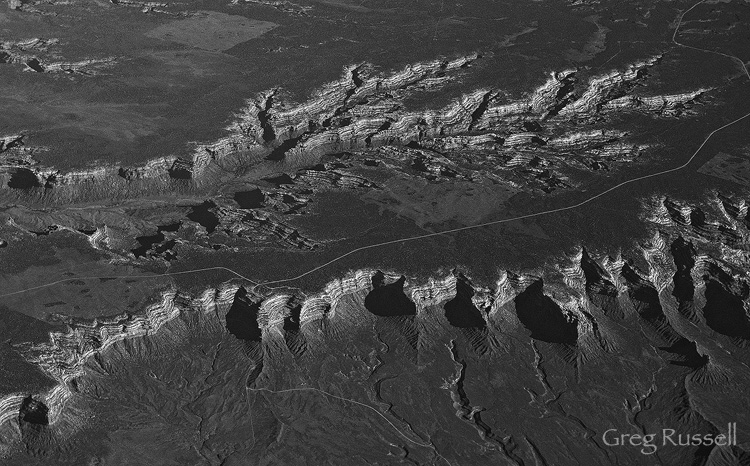

The Navajo or Diné Volcanic Field is a circle of volcanic formations lying roughly in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. These peaks and ridges are striking in their own right, but are even more curious because of their juxtaposition with our image of what the Colorado Plateau should be.

The Colorado Plateau is synonymous with sandstone. We identify this region by massive cliffs, arches, hoodoos, and towers; people come from all over the world because there is nothing like these places anywhere else on Earth. It seems a bit incongruous, then, to drive through this region past numerous large volcanic towers, all of which stand in stark contrast to the surrounding sandstone formations.

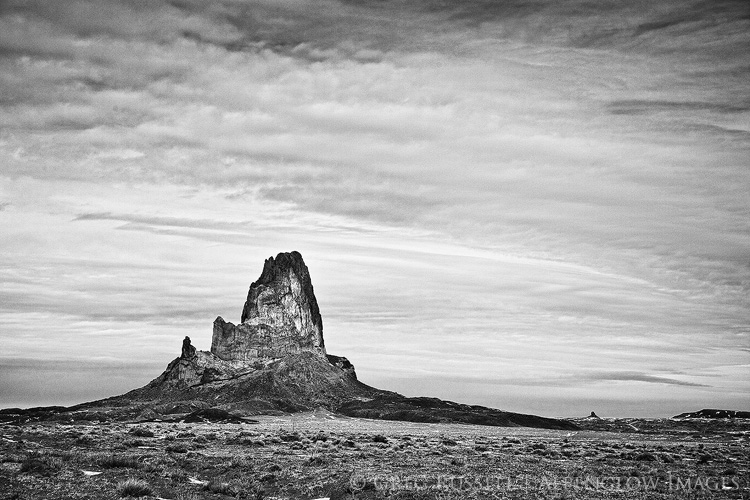

Black rocks protruding up

About 30 million years ago, as the rest of the Colorado Plateau was rising, several volcanic explosions occurred in northern Arizona and New Mexico. They occurred from Kayenta and Comb Ridge eastward to the Lukachukai Mountains and northwest New Mexico. From there, the semicircle of violent volcanic eruptions turned southward towards Zuni Pueblo. The plugs and dikes were covered for millions of years, but erosion has uncovered and sculpted these features, leaving behind the desert towers we know today. The Navajo simply refer to these towers as ‘black rocks protruding up’–tsézhiin ‘íí ‘áhí.

Diné ethnogeology

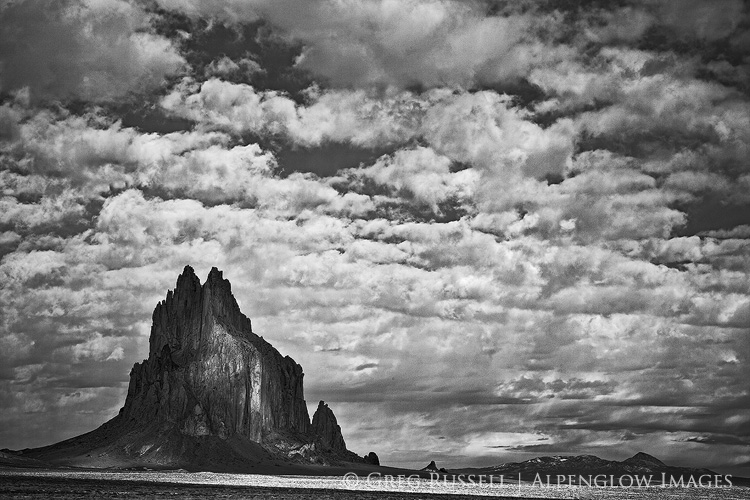

In spite of its obscurity in a sandstone world–or perhaps because of it–tsézhiin ‘íí ‘áhí has a strong presence in Diné mythology. Ship Rock–Tsé Bitʼaʼí–the landmark monolith in northwestern New Mexico, for instance, is told to have been home to a giant winged monster or bird, Tsé Nináhálééh. Tsé Nináhálééh was one of many monsters that followed the Diné to their current homeland–Dinétah–when they emerged to this world from the previous one. This bird was vicious, and would throw its prey into mountainsides and rocks, crushing them before eating them.

Monster Slayer (Nayé̆nĕzganĭ) was one of two sons of Changing Woman, Yoołgaii Nádleehé, who fought and battled these monsters. He had a magic feather that protected him from the giant winged monster’s attacks and was able to defeat it. Today, Ship Rock itself is thought to be the body of the winged monster; the volcanic ridges running out to its sides are thought to be the monster’s wings.

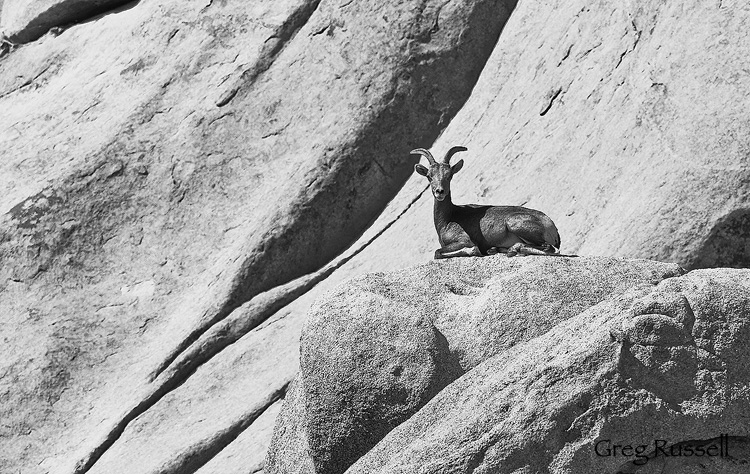

The Diné volcanic field is the perfect example of how geologic features and obscurities capture our attention and work their way into our cultural DNA. A region’s geology plays a huge role in its phenology, giving rise to many of the things we relate to in the places we love (trees, flowers, even animals), even if the geology itself goes unnoticed. Stories are told, and are passed down through generations. These stories are what root us in a place. This is another way we as photographers are very much storytellers.

This intersection between geology, folklore, and sense of place has really captured my attention lately and I hope to write more about it. In the meantime, how has geology influenced your sense of place?

*The Navajo Creation Story is one drawn from several stories, many of which can only be told respectfully during the winter months. There are several texts that have attempted to pull these stories into one cohesive book. An excellent summary can be found here.