I am writing this sitting at a desk that my dad made for my eleventh birthday. In the second drawer is an old pipe tobacco can–Captain Black–filled with Native American potsherds.

My family moved to the Four Corners region in northwestern New Mexico when I was six years old. Many of my earliest memories of New Mexico involve the typical sight-seeing outings families do; I remember going to Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. At that age, the significance of these world-class archaeological sites did not really mean much to me. However, I started to draw connections to the ancient residents of this area one September day while deer hunting with my dad; we walked through an area filled with potsherds. I was probably a little bored after several hours of hiking through the seemingly endless piñon-juniper pygmy forest, and the potsherds made for an exciting treasure hunt. We picked up some of the nicer ones and brought them home. Since then, they’ve largely lived inside of the pipe tobacco can inside my desk drawer.

I am not sure how old they are. Some are really lovely bowl rims, with simple triangular black-on-white patterns painted on them. Others are pieces of corrugated bowls. Many of the archaeological sites in that area of New Mexico are Navajo–about 400-500 years old. However, the areas we used to visit do not lie far from Salmon Ruins and the Great North Road. So, it is entirely possible–probable even–that these pieces are much older Ancestral Puebloan potsherds.

Archaeologists say that we learn best about ancient cultures by leaving artifacts in their place, admired but untouched. After all, they tell the stories of the peoples who came before us. Indeed, much science is lost by looking at these pieces of pottery ex situ. However, when I look at them, I think of the people who made them. What were they thinking when they left them? Did they walk away unflinchingly from their home, or did they take a longing look back, thinking they may someday return?

These fragmented pieces of pottery tell the story of a people who eeked a living off of the land, who knew the landscape and probably felt a deep sense of place here.

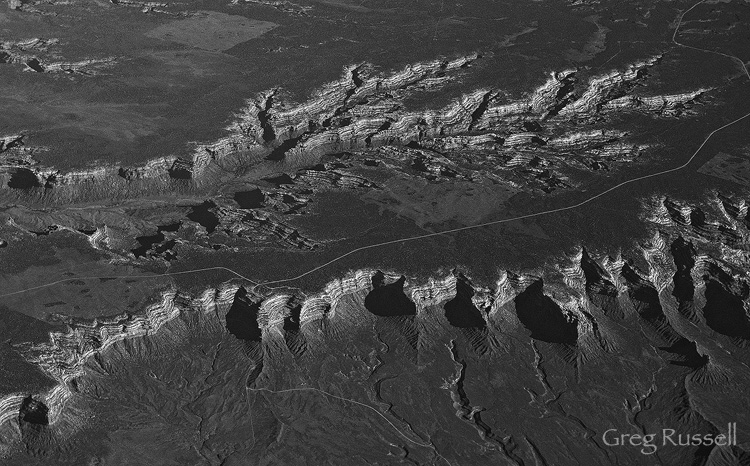

“I looked down upon hillside after hillside of slopes clear-cut for their timber. Traversed back and forth by logging roads, the hills were deeply scarred and patterened. All I could think of were pottery designs. Beginning there, the entire flight was an aerial Anasazi visual feast of basket weaves made of farmland plowing, river ways drawn out like rock art, and cloud patterns resembling rock forms.” — Bruce Hucko, Cave to Cave–Canyon to Canyon

Flying from my home in southern California to Colorado at 30,000′, I can relate to Hucko’s evocative impressions of the Western landscape (Bruce Hucko was the photographer for the Wetherill-Grand Gulch Research Project). I see landscapes–monoliths, cliffs, and mesas–that are part of who I am, so much so that I can recognize them without having seen them on a map, or even visiting them, in years. A floodplain in the Mojave desert, the Grand Canyon, the Vermillion Cliffs, Navajo Mountain, Cedar Mesa, Mesa Verde, the San Juans, the Sawatch, and finally we touch down in Denver. Terra firma.

Two hours in the air filled with fragments of landscapes that conjure memories–in the same way those broken pieces of pottery tell the story of a people, these landscapes are my potsherds of the American Southwest. This is where I have spent my life and I’ve had adventures with friends and family; these stories would fill a hundred books.

It has been over 25 years since my first visit to Chaco Canyon, but it feels like many more. It’s a sunny and warm December afternoon, and many of the other tourists have left, leaving the halls of Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito quiet and a little lonely and the moon is rising over Fajada Butte. I sit for a while, watching the reflected winter light bounce through the rooms, which are now open to the sky. For what feels like the hundredth time, I find myself thinking about the journey of the people who lived here, and of their great road north toward my childhood home, near Salmon and Aztec ruins. Potsherds lie across the high desert for nearly 100 miles; the stories of these travelers are being told in fragments.

So it is that we tell our own stories in broken, scattered pieces. Our own beautiful stories are being shared and discovered by the people in our lives, just as we discover our own pieces of others. If we are lucky we find an entire, unbroken, pot now and then.