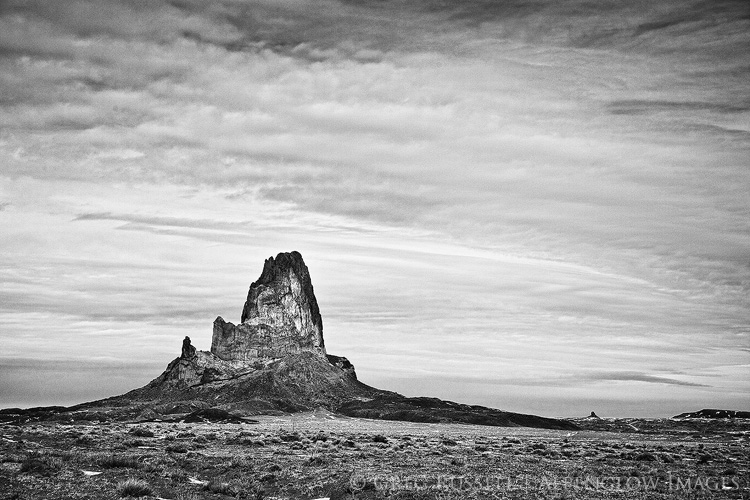

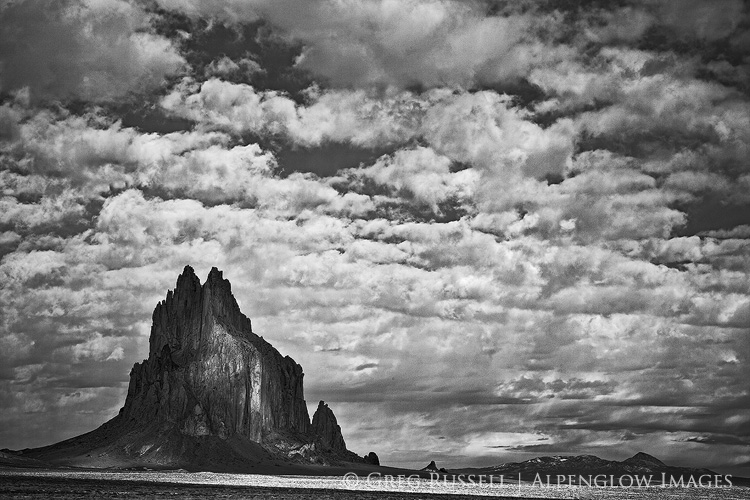

“The upper Escalante Canyons, in the northeastern reaches of the monument, are distinctive: in addition to several major arches and natural bridges, vivid geological features are laid bare in narrow, serpentine canyons, where erosion has exposed sandstone and shale deposits in shades of red, maroon, chocolate, tan, gray, and white. Such diverse objects make the monument outstanding for purposes of geologic study.” – Presidential Proclamation 6920 (establishing the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument), September 18, 1996

A wilderness of rock. That’s what I imagined the historic Boulder Mail Trail would be when my dad and I set off to backpack it last month. Indeed, to paraphrase Maynard Dixon, the upper Escalante Canyons expose the earth’s skeleton in a beautiful, if austere, way, exposing the earth’s skeleton.

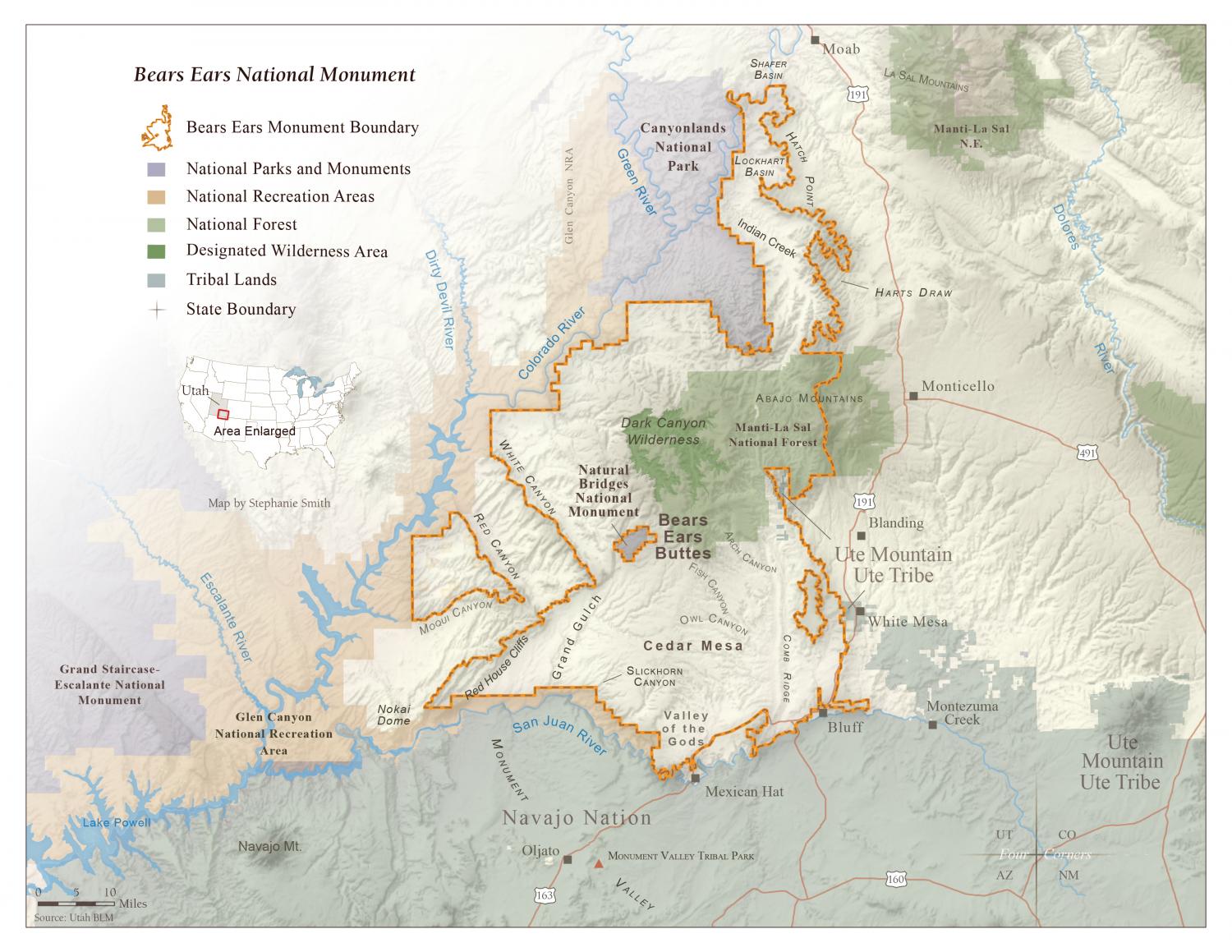

The Boulder Mail Trail (which isn’t much of a trail at all), is the historic mail delivery route between the hamlets of Boulder and Escalante, Utah. Highway 12, which now connects Boulder and Escalante, wasn’t paved until the 1970s, so the Mail Trail was the quickest route for quite some time. All along the route, the old telegraph wire connecting these towns is also very obvious, although it’s fallen down in a few places. The Mail Trail now lies almost entirely within the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

A couple of months ago, my dad asked if I wanted to go backpacking this spring, and of course I jumped at the chance. A while back, I wrote a blog post about January trips with my dad, and I continue to feel really fortunate that my parents are both willing and able to be active. It was our first backpacking trip together in many years, but it ended up being very fun, and just the right length for two old “geezers.”

For early spring, the weather was what one can expect on the Colorado Plateau: windy and cold. Out of the wind in the sun, it was pleasant, but it was never too hot. When we set off from the trailhead outside of Boulder, snow flurries were ducking in and out of the canyons on the Aquarius Plateau to the north, and looked like they might reach us within a few hours. Dark skies to the west seemed to promise wet weather as well. That’s better than boring blue skies, though, right?

The Mail Trail is more than just a walk across sandstone, as it crosses a few fairly large tributaries of the Escalante River. The most significant of these is Death Hollow, which despite the name is known for being a fun backpacking trip in its own right (save for the poison ivy it is also well known for!) and is about halfway along the Mail Trail. Death Hollow is surprisingly lush (hence the poison ivy), and is a wonderful riparian habitat tucked neatly away into the desert. We ended up camping in the bottom of the canyon amongst giant ponderosa pines because the weather was just spunky enough that we didn’t want to get blown off the rim and into the night as we slept. We ended up falling asleep early, and despite a small sprinkle of rain and major sandblasting from the wind, the storm never really developed.

The next morning, we hiked about a mile down Death Hollow before the route continued out the west side of the canyon, and towards Escalante. We were able to see Escalante within a few hours, but it took much longer to wind our way down through the sandstone and back to the car we had parked at that end of the Mail Trail. A quick run up to Boulder for the other car, and a beer (or two) at Hell’s Backbone Grill topped off the trip.

Despite the increased popularity of the Escalante area since President Clinton included it in his massive 1996 National Monument, the upper canyons of the Escalante River seem to be less visited than other more popular areas along the lower river. It was nice to be able to experience a little bit of history, wilderness, and complete solitude for two days. That said, solitude shouldn’t come as that big of a surprise–there isn’t a traffic signal for at least 100 miles from Escalante, and this is one of the most remote and rural places in the lower 48 states. Combine that with world class scenery, and this wilderness of rock is truly an area to be cherished.