Straight as an arrow, or very nearly so, the road crests the mountain range, beginning its descent into the valley. After what feels like only a few minutes, it will start up the next rise, repeating this pattern again and again.

Basin and range. Ascent and descent. This topography–narrow, steep mountain ranges separated by deep valleys–very nearly defines the West. John Muir’s Sierra Nevada is the westernmost “range;” the province then extends eastward, one towering mountain range after another, and would reach all the way to eastern Colorado if the Colorado Plateau didn’t get in its way.

Four years ago, my Dad and I began the somewhat informal tradition of making a January photography trip somewhere together. I think it started mostly as an excuse to be outside and hike around together, hopefully making a few images along the way. Last week, I found myself in his truck with him cresting the Amargosa Range thus beginning the descent into Death Valley.

Death Valley National Park typifies the Basin and Range Province; the Inyo, Panamint, and Amargosa mountain ranges rise like the vertebral columns of colossal ancient dinosaurs, and the valleys between them (Death Valley included) cut through the earth separating them. The changes in elevation are dramatic and impressive, even to someone not well-versed in geology. As the park brochure will tell you, it is indeed a land of extremes.

We spent the next few days hiking around some places I had been to before, and some I had not. As one must sometimes do in a national park the size of Connecticut, we also drove a lot. The arrival of a winter storm gave a unique patina to the desert: landscapes we normally associate with hot lifelessness were transformed–beautifully–by clouds and fog.

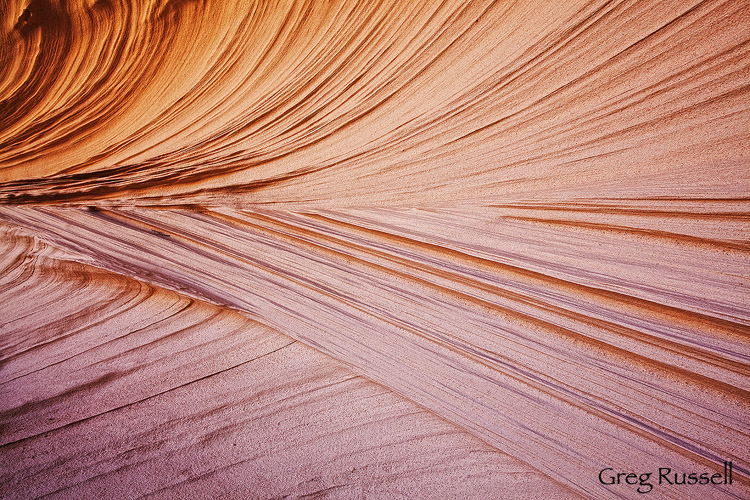

I don’t normally get to photograph über-dramatic light, and honestly I am okay with that. My eye naturally tends to find compositions in subtle light and delicate form, which is exactly what this storm gave us. This year I celebrated my birthday on our trip, and the light was a perfect birthday gift. So, not only was it a time to enjoy being outside, it was also a time of celebration.

The last four Januarys with my Dad have given me milestones by which to watch him get older as well. He is not in failing health, but with each passing year I see him–both of my parents–getting older. My rational brain is accepting of that, but the little boy in me isn’t quite ready for the aging process to begin–in them, or in myself. Over the last couple of days, I’ve been thinking a lot about aging, mortality, our ability to experience a place, and the creative process; I think a common thread runs between all of these things.

As photographers, and particularly as landscape photographers, our ability to create art is rooted in how we perceive the world: our ability to see light and distinguish shapes, and to integrate that sensory experience with the smells and sounds around us is the cornerstone of our craft. The most evocative landscape photography I have seen is that which is sensed, not only with my eyes, but inside of the nucleus of every cell in my body.

Our senses are rooted in our biology, which changes as we age. If our senses are changing, it is no surprise that our artistic vision would change as well. Ideally, it would mature along with everything else! I wrote in my last blog post about my own journey back in time, exploring my favorite images from the last half decade. My artistic vision has changed, certainly. Matured, perhaps. Practice, study, and introspection have no doubt played a part in this, but perception–the way my senses tell me about the world–is a huge part of that.

Do we perceive the world with more clarity as we age? Do my aging parents somehow see things more clearly than I do? In some ways, I’d like to think they do. It is somewhat macabre, but looking all the way to the end may help answer that. Turning to my “other” field of comparative physiology for a moment, the great Canadian physiologist Peter Hochachka wrote only days before his own death in 2002, “I have noticed how the mind seems to clear when one’s time is up and current life is near an end…instead of anger, bitterness or even sadness, there can be interest and increased clarity.”

Basin and range. On my birthday this year, this landscape gave me not only light, but hope as well. Hope that in 30 years, I will see this landscape differently, and with more clarity, as perhaps my Dad did standing next to me on this trip. Hope that I will still be creating images then, images that are personal, unique, intimate.