In my last blog post, I expressed a somewhat emotional response to the current threats facing our Western public lands. In this post, I’d like to provide a bit of context to some of the current threats, as well as the land transfer movement in general. It’s an especially complicated web of interactions and is really difficult to sum up in one blog post, so consider this an introduction. I believe that an understanding of these issues are something any Westerner should be aware of, as well as anyone working in the West (which includes landscape photographers, who have a vested interest in the preservation of wild space).

A look at our nation’s history

To understand what’s happening now in the West, we have to go back to 1862, and the passage of the first of the Homestead Acts. The Homestead Acts awarded 40-acre parcels of public land at little or no cost to homesteaders who were willing to improve it for agriculture for a period of 5 years. Because most of the public land lied in the West, this basically amounted to the opening of the frontier, especially in the wake of the Civil War, when later Homestead Acts were passed.

As anyone who has spent any time in the West can attest, it’s a hardscrabble place with little rainfall, and it’s difficult to make a living here. So, it’s no surprise that many lands were left unclaimed because of the barriers the landscape presented. Combine this with the entry of two large Western states–Arizona and New Mexico–into the union in 1913, and the federal government was left with a huge amount of public land to manage. Although the soil may not have been conducive to farming, and (lack of) rainfall may not have made grazing easy, minerals and timber were abundant, so the government ultimately created the US Forest Service (1905) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM; 1946) to manage much of these resources, and to ease the burden on the Department of Interior, which oversees the National Park Service.

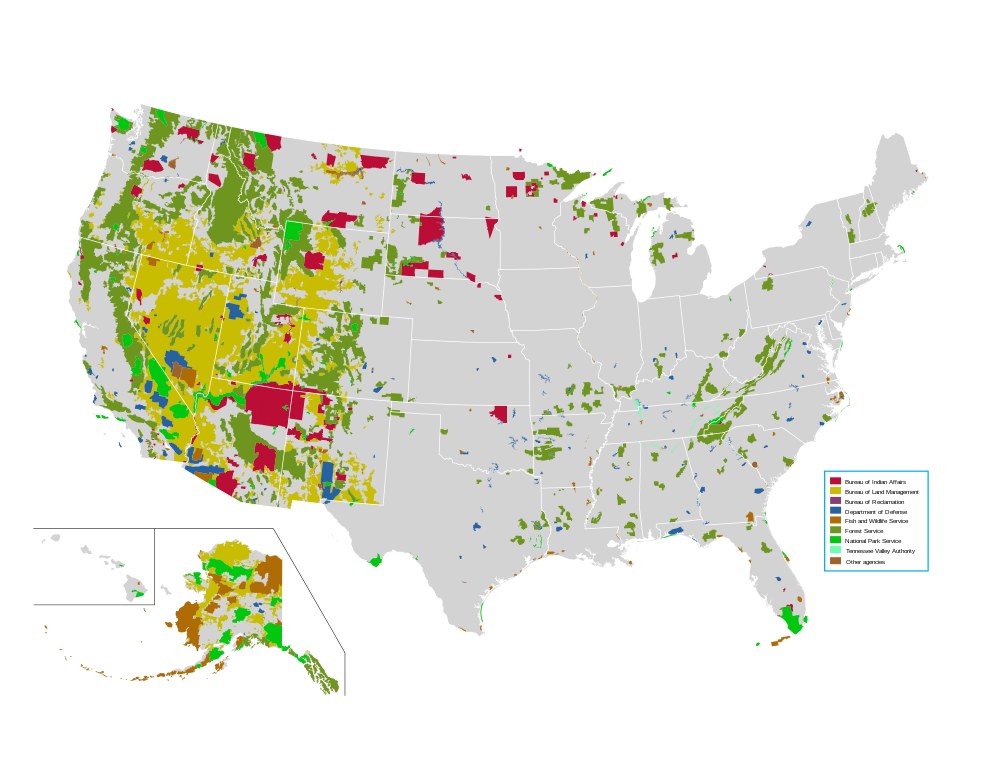

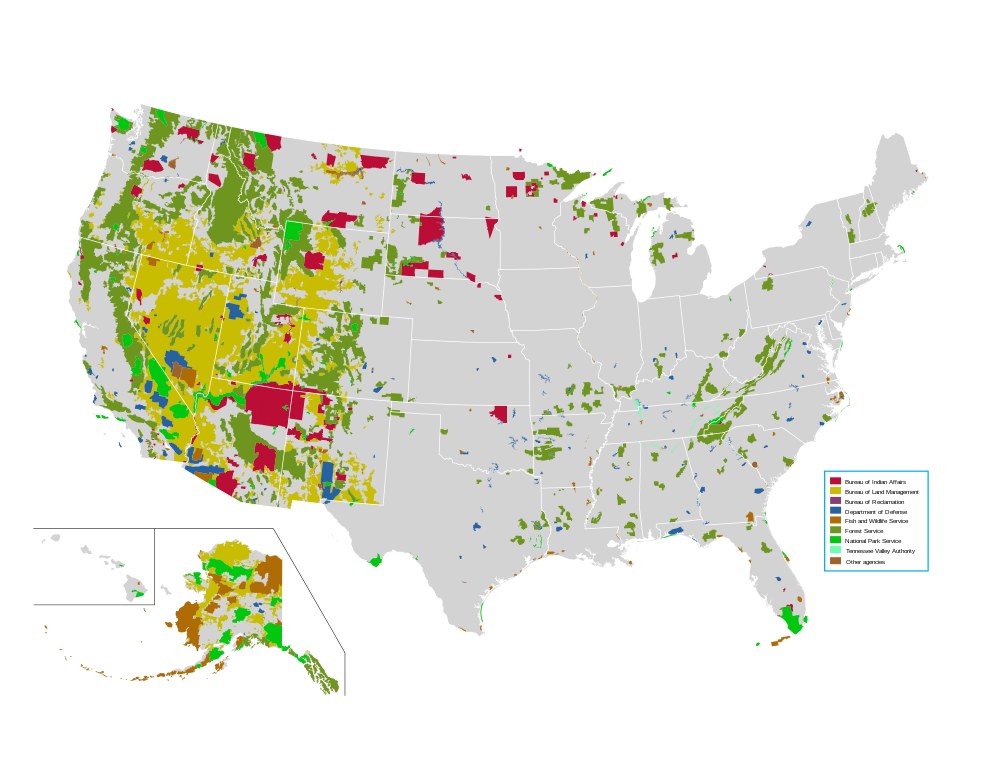

Let’s think about this for a moment. One of the things many Westerners identify with is a rugged individualism, the settling of the wild frontier. When the frontier opened during the nation’s reconstruction and the US government was basically giving parcels of land for free, Western culture laid down its roots. Within several decades, the US government, who was now in control of most public lands in the West (and still is, see the map below), needed a management plan. From the point of view of many homesteaders, this amounted to the government saying, “We gave you this land, and you settled it, but now we’re going to tell you how we want it managed.”

Most of the nation’s public lands are in the West. Public Domain image downloaded from Wikipedia

As you can imagine, a homesteader who was suddenly being told how the land they had been mining, or grazing their cattle on might be a little bit upset. So, to some extent there’s always been some level of anti-government sentiment in the West, which has been compounded by people who move to the West for added seclusion and an increased sense of isolationism. Indeed, such high profile incidents as Ruby Ridge, and even the car bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 have either directly or indirectly been the result of rugged individualism clashing with government oversight.

Land transfer & the Sagebrush Rebellion

While private development is not usually allowed on public lands, grazing allotments can be leased, there are some mining claims, and of course recreation is allowed such as hiking, rock climbing, photography, and hunting and fishing, although specific rules vary somewhat depending on the management agency, etc. For instance, no hunting or fishing is allowed in national parks.

In 1932, the federal government did try to transfer land back to the states, but in post-Depression America, states were concerned about having the funds to manage the lands effectively, etc. As a result they stayed under federal control. Today, the federal government pays states for the land that cannot be developed, and as a result, taxed. These payments in lieu of taxes can be a significant revenue generator for certain counties that have a large proportion of public land. Similarly, other sources of income like the ones resulting from the Taylor Grazing Act are important for certain counties (see reference below).

In 1976, in an effort to more explicitly regulate some of the above-mentioned activities on federal lands, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) that officially ended homesteading and formalized processes for regulating activities on federal lands, specifically those administered by the BLM. Within a year, the FLPMA had drawn enough ire from ranchers and miners that legislation was introduced into Congress that would transfer some land back to the states with the idea being that the land could be managed more directly for the sake of individual interests there. This legislation–which was introduced twice but did not pass–was the birth of a movement known as the Sagebrush Rebellion.

Where are we now?

Since the late 1970s the Sagebrush Rebellion hasn’t really garnered much attention per se, although there have been some very high profile incidents that revolve around the federal government and disagreements with private citizens (The standoff at the Bundy Ranch in Nevada and the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon are two of the most well known). Despite the fact none of these incidents have resulted in major legislative changes, there is the argument that they really are counterproductive to their stated original intent (see here and here), driving wedges where they don’t really belong.

That ‘stated original intent’ is also a bit cloudy. When you dig into the web of what’s morphed from the Sagebrush Rebellion into the Land Transfer Movement, things get confusing fast. Ranchers aren’t the only concerned parties it seems, but militia members and “alt-right” conservatives also seem to have a vested interest in returning public land to the states or private parties. Similarly, members of Congress also have ties to groups like the American Lands Council (which has a misleading name but is the biggest proponent of the Land Transfer Movement).

Most recently, representative Rob Bishop from Utah introduced the Public Lands Initiative to Congress, which would have returned public lands in Utah to state control; fortunately it was not voted on before Congress ended their session in late 2016, effectively killing the bill.

What’s the big deal, and what next?

With all of these failed attempts to return Western public lands to state control, why should you care? There are several reasons. First, the vocal minority who are perpetrating the highest-profile standoffs with government officials are becoming increasingly violent. Threats to public lands employees are becoming more common. Second, while this legislation has failed in the past, it doesn’t mean it always will. Rob Bishop is the chairman of the House Committee on Natural Resources, and advocates development of Utah’s wild places. Sooner or later, he’ll catch the ear of influential people who can make things happen. This is underscored by the fact that it’s becoming clearer that the Land Transfer Movement is incredibly well funded.

Lands transferred to state or private control do stand a higher chance of oil and gas or large scale mining development, among other things. This would make it more difficult to pass legislation fighting global warming, and thus would set heartbreaking precedents, and do irreversible damage to our Western landscapes. A common response I’ve seen to these threats on social media is, “It’ll never happen!” Maybe not, but the stakes are simply too high to sit back and assume it won’t happen.

There is hope, though. Although a vocal minority is favor of the transfer of Western public lands, the majority of Westerners are not. This was well illustrated just last month in Nevada’s general election as well as in the Montana governor’s race. As Westerners we all need to be educated, and see through the politics, and look for common ground together. Very few of us would disagree that there is room on public lands for everyone–grazing interests, hunters, photographers, backpackers, etc. None of us want these magnificent landscapes spoiled.

As photographers what can we do? I have several ideas. First, you can donate your images to worthy nonprofit groups (e.g., the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance or Grand Canyon Trust). If that is financially prohibitive, consider donating a portion of your proceeds to these causes, or to the support of quality journalism. Second, tap into your local community. Learn what the land use issues are, and how your images can support groups advocating for your position. Similarly, take advantage of public comment periods on these issues (and use your images to support your comments). Third, build bridges outside of your box. Hunters and anglers are equally as vested in the land as you are–how can your images help advocate for issues important to them?

This is just a start–feel free to offer more ideas in the comments.

References

Read the Homestead Act of 1862 here.

An in-depth history of in-lieu programs for western federal lands can be found here.

Read the Federal Land Policy and Management Act here.