As we board the homeward bound flight, the sun is setting over the Rocky Mountains, reminding me of my early childhood years living in Denver. The sunset becomes more intense as the plane is pushed onto the runway, and takes off, leaving Denver International Airport behind. The beauty of flying westward into the sunset is that it lasts longer–the earth’s shadow and Belt of Venus seem to be eternal, keeping me company as I daydream looking out the window over my sleeping son’s head.

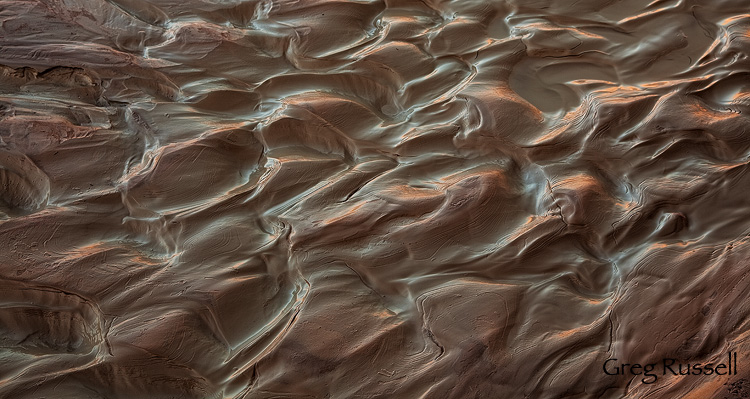

Below us, lights from the small towns of the West are starting to come on. I wonder what’s happening in those towns on this Friday night; people are relaxing at the bar after a long week of work, teenagers are cruising Main Street looking for something to do. Despite that, its the empty spots, the growing blackness, that capture my imagination. I’ve been a passenger on this route enough times to know what’s below me: the foothills of the western slope of the Rockies, the Green and Colorado Rivers, the white rim of Canyonlands, the Grand Canyon, the Mojave Desert.

Its quite possible there’s not a whole lot of unexplored areas left in the West, but part of me wants to hang on to the notion that there is still some “out there” left out there. David Roberts recently had a thought-provoking op-ed piece in the New York Times arguing that with 21st Century technology, there’s not a whole lot of wilderness left. That hopeful naïveté I cling to wants to disagree with him–that possibly there is still an unexplored canyon, or at least a hill which offers a great view of this everlasting sunset–that has yet to be enjoyed.

Aldo Leopold wrote,

“To those devoid of imagination a blank place on the map is a useless waste; to others, the most valuable part.”

Tonight, sitting on this jet with a bird’s eye view of the West, I have to wonder where my imagination would wander if there were no blank spots on the map. As a photographer, I have been thinking a lot lately about documenting these wild lands–what is my responsibility as an artist, my obligation to protect these lands? If those peaks and mesas are leveled, if lights begin to dot the landscape, these places will change forever.

Where does your imagination wander? None of us would argue over the value of those blank spots on the map, but what do you think–is there a fine line between artist and activist, or are they one and the same?