Just a few posts ago, I mentioned how I spent several summers working in the White Mountains of eastern California when I was in graduate school. The Whites are an interesting mountain range. Comprising the eastern border of the Owens Valley, they are certainly imposing, with California’s 3rd highest peak (White Mountain Peak, 14,252′) as well the highest point in Nevada (Boundary Peak, 13,147′), but despite their prominence, the Whites are visited far less than the nearby Sierra Nevada.

The Sierra is a relatively wet mountain range, receiving anywhere from 20-80 inches of precipitation a year (for the arid west, that’s wet). The Whites, in the rain shadow of the Sierra, stand in stark contrast, fully embodying the characteristics of the Basin and Range province, to which they are included–dry, windy, desolate, and strikingly beautiful.

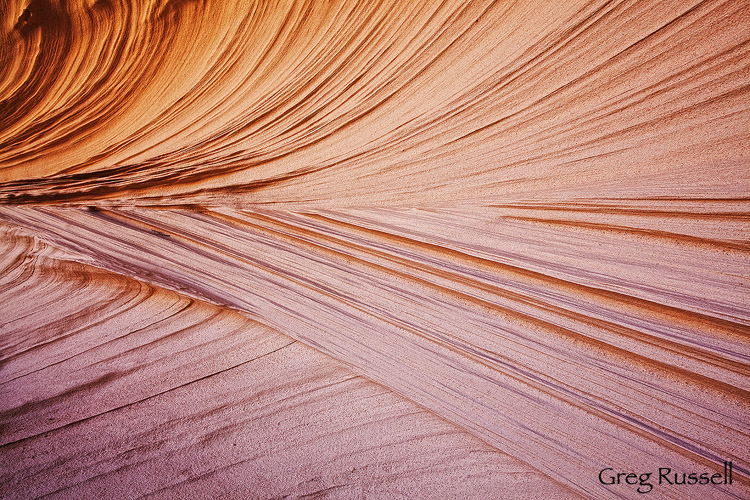

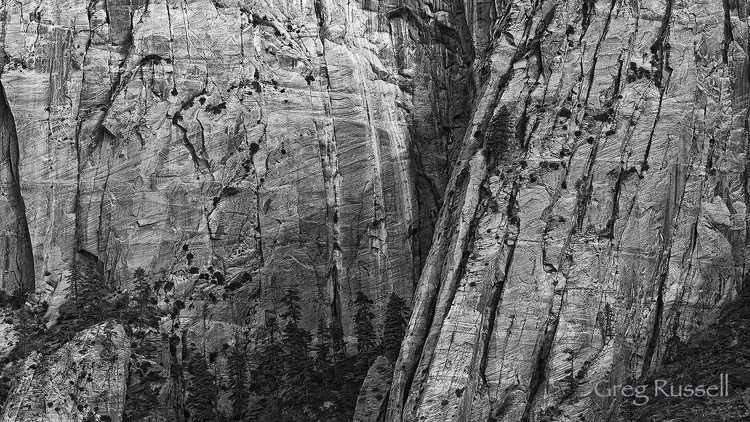

I have always loved the Whites, primarily because the lower elevations remind me of my home in northwestern New Mexico: piñon-juniper scrubland and sagebrush dominate the landscape, giving way to primarily lower-growing sage above about 8,000 feet. Deer, coyotes, wild horses, pika, and marmots are common here. However, the real draw–accounting for the bulk of visitation–is the presence of the Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva). With the exception of organisms that self-replicate (clones), bristlecones are the longest-living organisms on earth. One tree in the Whites, Methuselah, is estimated to be 4,500 years old. If the Whites have a persona of incredibly difficult growing conditions, then the bristlecones fit that quite well. Their gnarled trunks and otherworldly shapes are a favorite of photographers.

After nearly seven years away, I recently returned to the White Mountains. Walking around in the ancient bristlecone pine forest is an act of humility. Before leaving on my recent trip, a friend and I had a conversation about life and the value of living in the moment. This conversation was heavy on my mind as summer storm clouds moved through the Whites at sunset, giving these grand trees an equally grand backdrop.

Of all things on earth, these trees have given their best shot at living forever, and even they can’t quite do it. Once they die, the dry air preserves them leaving funky skeletons on several hillsides. What advice would they give, after 4,500 years, to someone just starting out? Would it be to live in the moment, to not let the little things get you down, and to hold close the things in life that make you deeply happy?

I’m anthropormorphizing a little bit more here than my contract allows, so I’ll stop. Suffice it to say, I think that’s pretty good advice.

We spent one night at 11,000′ in the bristlecones, and I was reminded of a few things that have kept the White Mountains on my mind all these years:

- Yes, it can snow in July in California. Even if only for a few minutes.

- The White Mountains are the only place I’ve ever experienced altitude sickness (manifested by trouble sleeping). I attribute it to the dry air.

- The warm-toned trunks of the bristlecones contrast very nicely with stormy skies.

- Everyone should experience quiet like the Whites afford once in their lifetime.

- Everyone should experience a night sky like the Whites afford once in their lifetime.

From a photographic point of view, I find it amazing that several images can come out of one place in a short amount of time. This is probably due to luck, inspiration, and visualization, but I have been updating my portfolios with new images and have added several from the White Mountains. Please visit my Mountains and Intimate Perspectives portfolios to see these and other new images.

It’s funny how some places can be a huge part of our lives, exit for several years, and then re-enter. I guess they never really leave us.