If you keep up with my blog, or if you’ve purchased our ebook, An Honest Silence, some of the themes in this essay, even some of the direct words, will seem very familiar to you. I consider all of these thoughts an ongoing synthesis of experiences, and the repetition–in my mind–is part and parcel of the evolution of these thoughts. My apologies if it seems derivative.

As we board our homeward-bound flight, the sun is disappearing over the Rocky Mountains, reminding me of my early childhood years living in Denver. The sunset becomes more intense as the plane is pushed onto the runway, takes off, and moves quickly over the Front Range, leaving the city lights behind. Flying westward, the Earth’s Shadow and Belt of Venus seem to be unable to let go of the day, keeping me company as I look out the window over my sleeping son’s head.

Below us, lights from the small towns of the West are starting to come on. However, the empty spots—the growing blackness between the towns—are what capture my imagination and attention tonight. I’ve been a passenger on this route enough times to know what’s below me: the foothills of the western slope of the Rockies, the Green and Colorado Rivers, the white rim of the Canyonlands, the Grand Canyon, the Basin and Range province, and eventually John Muir’s beloved Range of Light.

Like so many others, I first discovered these places while on summer vacation with my family. We drove through the national parks and along lonely highways, filled with buttresses, canyons, peaks, and monoliths; they stuck in my memory as I returned home, and I read everything I could get my hands on about the adventurers who explored these wild, remote, isolated, and dangerous locations. As often as I was able, I ventured out in search of my own adventure.

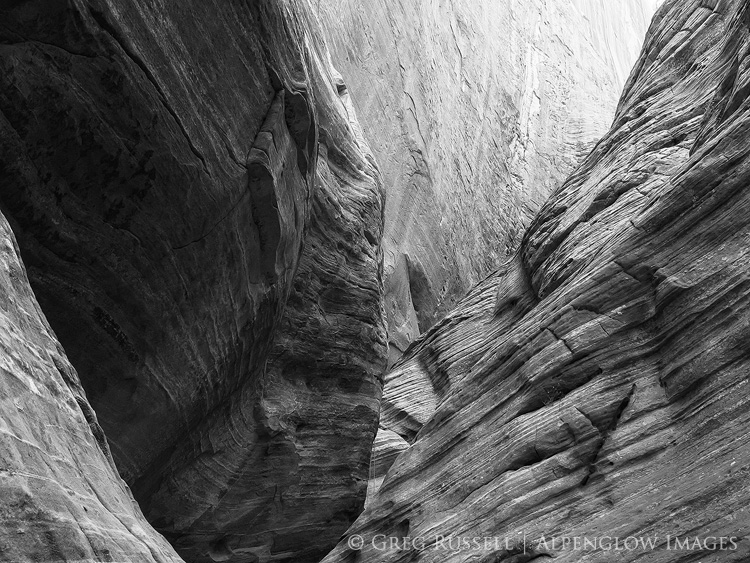

Today, more than 20 years later, I am finally beginning to understand the value of both wilderness and wildness in our lives. The architects of the Wilderness Act envisioned wilderness as a place “untrammeled by man,” essentially to remain a blank spot on the map. Indeed, we find ourselves in a world where we try to be big. Everywhere, we are connected—via 3G—to the civilization that surrounds us, the number of empty places we experience is decreasing rapidly. When we take the courageous leap, hit “Command-Q” on our keyboards, and venture out into these blank spots on the map, we are able to acknowledge that we are indeed small in this world, that we are connected to—not isolated from—nature.

Our nation’s Wildernesses represent much more than acreage and species diversity—things that can be quantified. They offer a place for us to experience a quality of life—the wildness Thoreau wrote about in his now famous passage, “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” Earlier this year, a close friend was backpacking alone in a California Wilderness area; his first evening out, he realized he was being stalked—at close range—by a mountain lion. It was a long, sleepless night for him, but everything turned out all right. Facing the prospect of moving down on the food chain, my friend experienced a visceral, almost ancestral, reaction to the wilderness. We should all be so lucky. We go to the wilderness to find true wildness, and while it may come in forms that sometimes surprise us, hopefully we will come out kinder, gentler, sweeter human beings.

(Thoreau believed that we should embrace this sort of wildness on every walk in nature. In his essay Walking, he wrote, “We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return; prepared to send back our embalmed hearts only, as relics to our desolate kingdoms. If you are ready to leave father and mother…never to see them again…then you are ready for a walk.”)1

After nearly a quarter century of wandering our nation’s wilderness in search of excitement, solace, adventure, and myself, I am watching my son discover his own wild nature through play in the outdoors. In observing him, one becomes keenly aware that there is a quality of wildness in the wilderness experience. Much emphasis today is placed on protecting wilderness as a parcel of land, but saving our own wild nature is just as important. In wildness is the preservation of us.

Aldo Leopold wrote, “To those devoid of imagination a blank place on the map is a useless waste; to others, the most valuable part.” Tonight, sitting on this jet with a bird’s eye view of the West, I have to wonder where my imagination would wander if there were no blank spots on the map. If the peaks and mesas below me had been leveled, if more lights dotted the landscape, these places—as well as our experience of wild nature—would change forever.

1I do not completely agree with Thoreau; I do not believe we need such harrowing experiences to appreciate either the Wilderness areas that have been set aside by Congress, or to understand our own wild nature. First, encounters like my friend’s have the tendency to make all but a few people fearful to be in the outdoors, and the preservation of wildness is diminished dramatically if we pit ourselves against perceived dangers, whether biotic or abiotic—the Other. We share common elements with all of nature that are billions of years old, elements forged in stars that are light years away; we have a primal connection to the landscape and its creatures. Acknowledging and embracing this is perhaps the ultimate act of courage and humility—the first steps in realizing our smallness in the world. Second, I believe we need wilderness because of the connection that is fostered, as Wallace Stegner wrote, “even if we never once in ten years set foot in it.” Knowing it’s there gives our daydreams a place to drift to, maintaining sanity and health.