I recently did a solo backpack into southern California’s San Bernardino Mountains. My primary goal was to climb San Gorgonio Mountain (11,503′), the tallest point in southern California; my secondary goal was to escape the searing heat in the valleys below. On August 11, I’ll have lived in southern California for ten years (as a somewhat macabre coincidence, August 11 is also the ten-year anniversary of Galen & Barbara Rowell’s death), and I decided it was finally time to climb this formidable mountain.

Over the past decade or so, I have not really climbed mountains for the sake of climbing mountains. In college, I used to drive down to Colorado and climb 14,000′ peaks a few times a year, but I seem to have gotten away from that. I suppose the time period that I stopped doing long hikes was also the time I got into photography. In some ways, the two don’t really dovetail well–long hikes require early starts and the pace can be, “go go go” for hours on end; when you’re in the mountains, a 16-hour day isn’t uncommon. Photography, on the other hand, calls for quiet contemplation. It can be a tough balance.

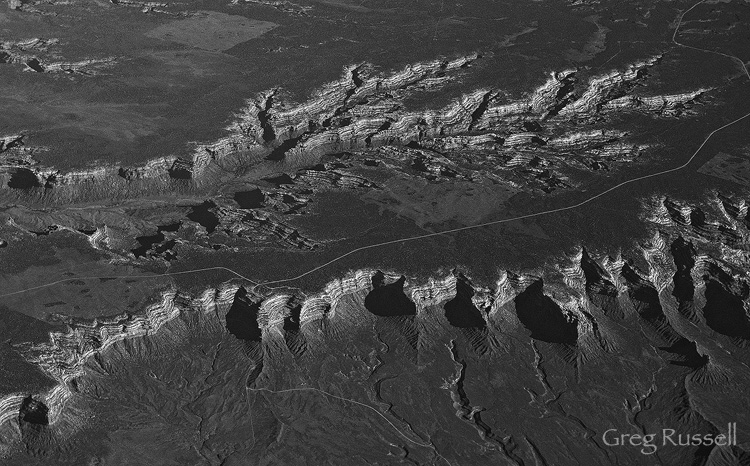

San Gorgonio Mountain, 11,503′, January 2011

This disconnect has bothered me, and like so many other insignificant problems, I’ve let it stay on my mind longer than it really should. I’ve largely solved the problem by carrying with me a small point-and-shoot camera that can capture images in RAW format, still giving me the ability to edit them, but also giving me the flexibility to pursue more difficult and athletic outdoor pursuits. There is, of course, the tradeoff of image quality when you use a point-and-shoot over a DSLR, but it is one I was willing to make.

When I was in college, I read Robert Pirsig’s, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I’m not sure I completely understood it, and even if I reread it today, I’m not sure I would. It’s pretty far out there, and it’s deep. However, the theme of the book–quality–has been on my mind since. Every time I go into an outdoor store, I drool over all the sexy new gear, and sometimes I succumb to advertising, but I pride myself on my really old equipment. For instance, I’ve been using the same backpack for over 20 years now, and it’s still going strong, after 1,000s of miles. I used my nifty point-and-shoot camera to for some self-portraits to highlight the pack in action on my recent trip to San Gorgonio Mountain. Despite my allegiance to my gear, the specter of consumerism hovers near me most of the time.

20 years old and still going strong, self-portrait, August 2012

(click on the diptych to see it full size)

“All that matters is that you spare yourself nothing, wear yourself out, risk everything to find something that seems true.” –Tony Kushner

To summit San Gorgonio Mountain, I got up at 3:30am, and was on the trail by 3:45. From my campsite, I was able to summit at 5:30am, just before the sun came up. I used the self-timer on my camera for a few self portraits, and then headed back down to my campsite for a cup of tea before packing up and heading back to my car. The morning was cool, and I forgot how long the Earth’s shadow and Belt of Venus seem to hang in the sky at this elevation. Even though I could see the megalopolis of southern California stretching below me, I had this mountain completely to myself.

Predawn light, San Gorgonio Mountain, August 2012

On my hike down I thought about the physical act of climbing mountains as well as the mountains we climb within ourselves. “Like those in the valley behind us,” wrote Robert Pirsig, “most people stand in sight of the spiritual mountains all their lives and never enter them, being content to listen to others who have been there and thus avoid the hardships.” I thought about my point-and shoot camera, my 20-year-old backpack, people in my life, and the mountains we all find ourselves challenged by every day.

I am happy that I finally ventured into the San Bernardinos to climb San Gorgonio Mountain.

Mt. San Jacinto as seen from San Gorgonio Mountain, August 2012

Krummholz, Jepson Peak, and the Earth’s Shadow, August 2012