As the urban/rural boundary has blurred over the years, I’ve come to see that growing up in the city had its rewards. The inner-city life has adventures all its own, but I was also lucky to have grown up in the city when I did, when there was still some open space around – untended little wild spots, overgrown orchards, vast open fields that seemed to stretch forever without a building, dense arbors in urban parks where we could hide securely from school and cops.

-Ernest Atencio

Open space was a huge part of my childhood. Every day after school, my friends and I would gather at the vacant lot near our houses, building jumps for our bicycles that were destined to break at least a few bones (although somehow they never did). We went home only when our parents came looking for us.

For those few hours after school each day the city we lived in seemed to melt away, and we could pretend to take our bikes to anyplace in the world we wanted.

As we grew older, we ventured further from our neighborhood, eventually making our way out to the piñon-juniper woodland that surrounded my hometown in northwestern New Mexico. There, we encountered coyotes, deer, as well as mysterious noises in the bushes that were probably nothing more than a deer mouse scurrying around, however it was enough to stir the remnants of an overactive childhood imagination.

So it was that my formative years were not spent in ‘wild’ wilderness necessarily, but it was wild enough to spark my curiosity, to make me want to see more wild places, and to instill in me a sense of adventure and stewardship. It was in those pygmy forests of the Four Corners that my lifelong relationship with wilderness was born.

“Without any remaining wilderness we are committed wholly, without chance for even momentary reflection and rest, to a headlong drive into our technological termite-life, the Brave New World of a completely man-controlled environment.” writes Wallace Stegner in his ever-poignant Wilderness Letter.

Stegner continues, “We need wilderness preserved–as much of it as is still left, and as many kinds–because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed. The reminder and the reassurance that it is still there is good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it. It is good for us when we are young, because of the incomparable sanity it can bring briefly, as vacation and rest, into our insane lives. It is important to us when we are old simply because it is there–important, that is, simply as an idea.”

What Stegner is saying is that every one of us needs wilderness. I worked for several summers doing biological data collection in the White Mountains of eastern California. One summer a volunteer in our lab came to the field with me for the first time; he grew up and spent almost his entire life in Los Angeles.

After leaving the pavement, he said to me, “I didn’t know there were any dirt roads in the U.S.” That day, things I naïvely thought were commonplace appeared as a whole new world to him: deer, hawks, wild horses, violent but brief thunderstorms, and views that stretch on forever transformed his perception of the world before my eyes.

This is the wellspring of my hope. Everyone perceives “wilderness” differently, and we have all been introduced to it in different ways. We all have our own personal reasons to fight for its protection. Yet, we need it, according to Stegner, for our spiritual health.

Our spiritual health.

Perhaps it is something rooted deeply in our evolutionary past, but wilderness is healing, a place of solace and comfort. As far as efforts to protect wilderness go, we as a people have unity in our diverse perceptions of wild places. Some wildernesses are little, some are big, but they are all equally valuable.

I wonder what those piñon-juniper forests of my youth would look like today, seen through older eyes. I know at least some of it has gone away to make space for homes. However, selfishly, I like to think they remain a place of hope, sanity, imagination, and peace. Who knows, maybe some kids are building their own bike jumps there right now. That may not be such a bad thing.

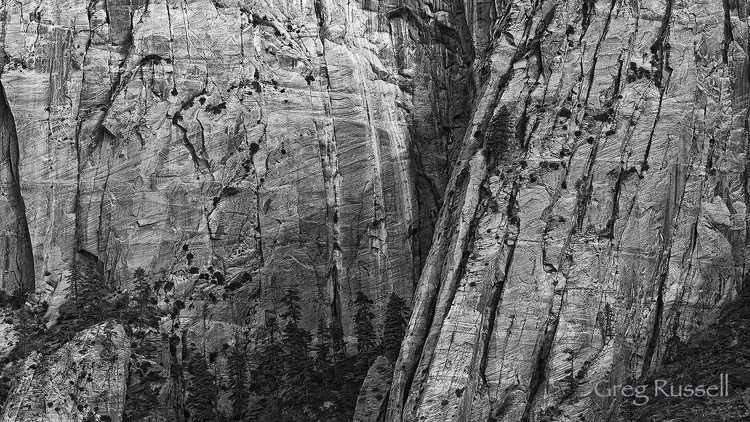

When it comes to things I care deeply for, words sometimes fail me. I make photographs that (I hope) express my emotions for wild places.

What experiences formed your relationship with wild places? Where are the places you seek comfort?