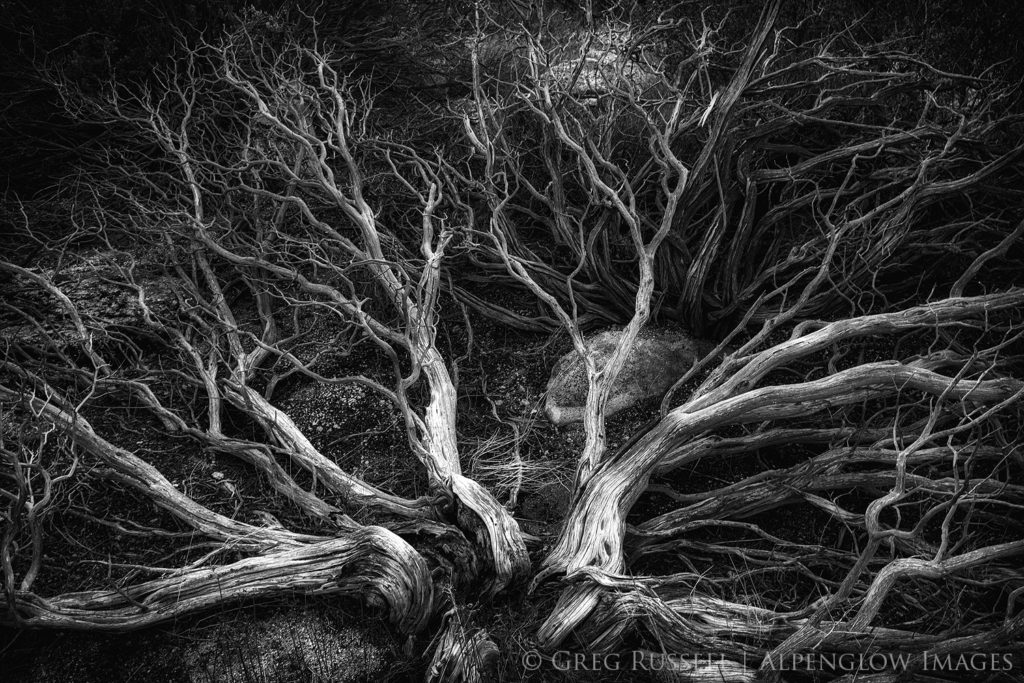

Writing this, I can hardly believe 2021 is behind us. It sounds cliché, but it feels like just yesterday I was taking a look back at 2020, and yet here I am writing a 2021 retrospective. While this past year brought more freedom of movement, it wasn’t without uncertainty. Still, I was able to get outdoors, especially in the early part of the year, to work on my Wilderness Project. It has become more of a slow meditation on the wilderness areas close to my home, and while I’m nearing its end, I’m admittedly a little sad about it, so I’ll draw it out longer than is probably necessary. Being able to explore and discover my “home territory” has been immensely rewarding.

I was able to experience exceptional weather conditions this year in my home desert, the Mojave. Being able to see what’s already a beautiful landscape in its winter coat was a highlight of my photographic career. The Mojave Desert, and especially Joshua Tree National Park, has become part of who I am, and owns a significant portion of my photographic voice. I wrote about my 20-year relationship with Joshua Tree earlier this year in On Landscape Magazine.

On Rediscovery

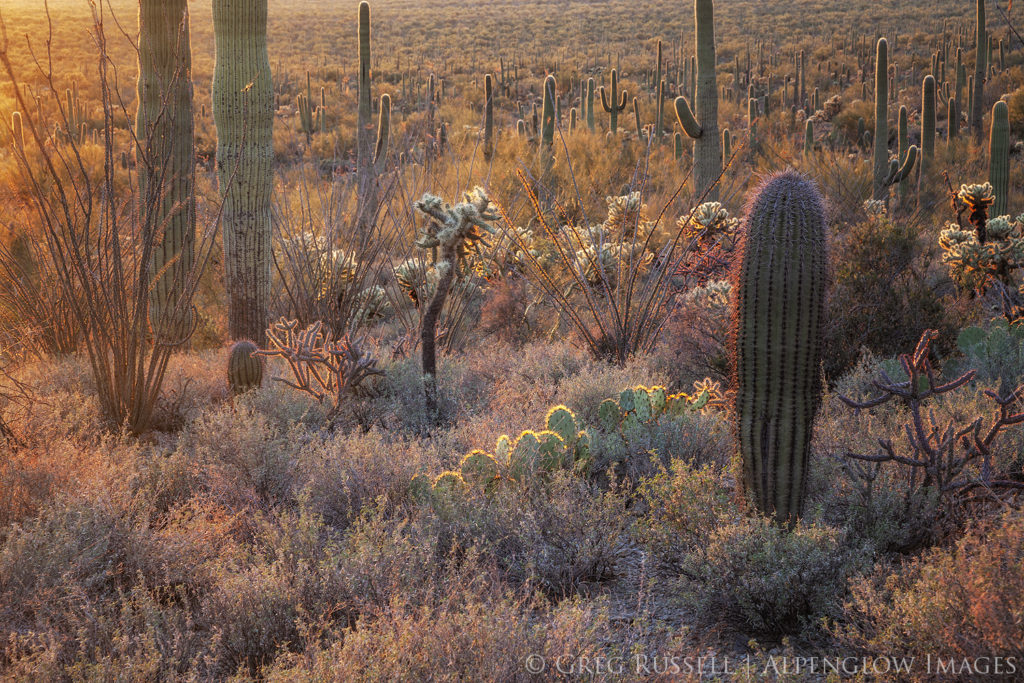

This year was also one of joyous rediscovery. Years ago I had visited the biologically diverse Sonoran Desert with a friend, but the landscape had sort of been lingering somewhere deep in my memory, not really coming to the surface. Being able to travel a little more confidently this year (thank you vaccinations AND boosters) gave me the opportunity to spend some quality time in southern Arizona. This is a landscape that will really make your heart sing, and I’m looking forward to spending much, much more time there in the future.

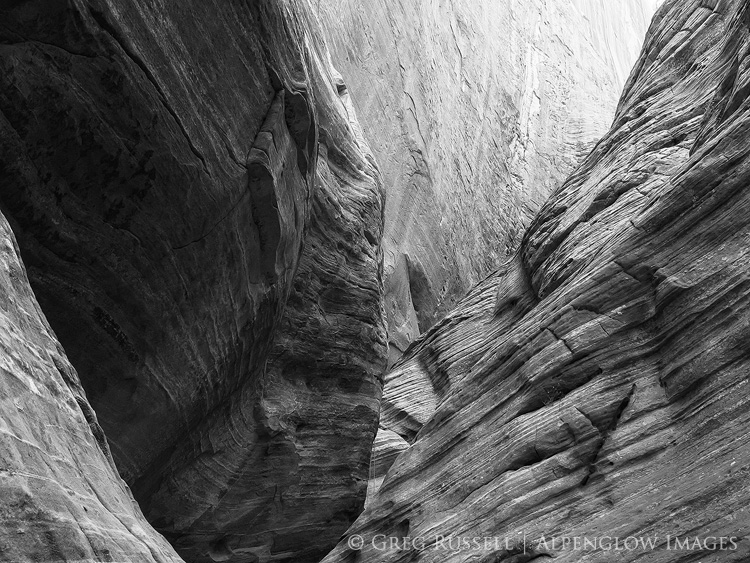

In the spirit of rediscovery, I also completed a backpacking trip that has been on my list for a long time in central Nevada. The Toiyabe Crest Trail runs along the crest of its namesake mountain range. The Great Basin is incredibly beautiful–as much as Colorado, I’d argue, except it’s browner and the highways are straighter. The Toiyabes are no exception, and they receive virtually no visitation making the trail exceptionally difficult to follow. Truth be told, this was an amazing trip, but it became an intensely physical endeavor, with photography taking a backseat. Also, smoke from the West’s many wildfires obscured any grand landscapes anyway. Ah, climate change!

I wish you the very best 2022 has to offer!

Let’s get on to the images

Past images of the year:

2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020