I remember my first trip to the Grand Canyon in 1992–it was not only my first backpacking trip ever, but also my first memorable trip to a national park. We went over spring break, in late March, and it was snowing hard at the South Rim when we arrived. I remember being cold and wet the night before our hike began, being completely terrified on the icy (and steep) South Kaibab trail the following morning, and sweating as we walked into Phantom Ranch later that afternoon. The rest of the trip was rainy, often very cold, and wet.

Despite all of that, I had a great time. A funny thing happens after outdoor experiences like this one: we seem to forget all of the “bad” parts of a trip, remembering the good things. Do the bad experiences really go away? Not completely: We learn from them. As a novice backpacker, I learned several things about hiking in poor weather; I learned them the hard way, but I survived.

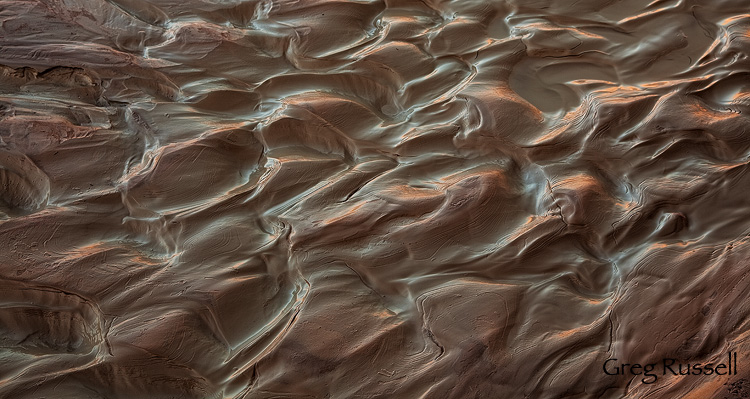

The thing that stuck in my memory more than anything else from that first trip to the Grand Canyon was the magnificence of the place. The sheer drops, layers of sandstone, and of course the power of the Moenkopi-colored mud flowing in the Colorado River. I’ve returned to the Grand Canyon more than almost any other national park. During my first trip it was simply breathtaking; since then it has become breathgiving.

Since 1992, I’ve backpacked the Grand Canyon once more, and have camped on the rim multiple times. Each time I say to myself, “Why don’t I visit more often?” Yes, its packed with people, especially on the holiday weekends when I find time to visit, but there’s a magnificent peacefulness that surrounds it. There are small pockets, places, you can go and hide, and despite the hordes, its almost as if you have this huge amphitheater to yourself.

Just like so many other geologic wonders on the Colorado Plateau, there really is nothing like the Grand Canyon on earth. Although I’ve enjoyed it for 19 years, I just now have images of it. Click the image or here to see the rest.

Most of us, I think, lie somewhere along this continuum. Most people are constrained enough by time (i.e. other commitments in life) that they can’t always wander as much as they’d like. Personally, I do rely on guidebooks and word of mouth to help guide me to pretty locations, but once I’m in the area, I very often will wander, looking for unique compositions. Fortunately, most of these locations are really conducive to letting creativity flow.

Most of us, I think, lie somewhere along this continuum. Most people are constrained enough by time (i.e. other commitments in life) that they can’t always wander as much as they’d like. Personally, I do rely on guidebooks and word of mouth to help guide me to pretty locations, but once I’m in the area, I very often will wander, looking for unique compositions. Fortunately, most of these locations are really conducive to letting creativity flow.