I’ve often (somewhat seriously) joked that the only reason I’d want to be the President of the United States is because of the Antiquities Act. This law enables the President–with the swipe of a pen–to protect our nation’s “antiquities” by declaring a national monument. Theodore Roosevelt, who signed the bill into law, used the Antiquities Act to create Devils Postpile National Monument, as well as Grand Canyon National Monument, which would later become a national park. Most boys want to be an astronaut when they grow up; I wanted to create national monuments.

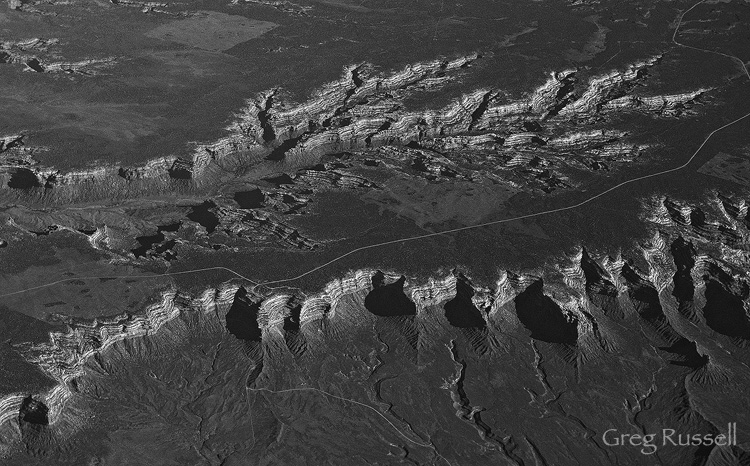

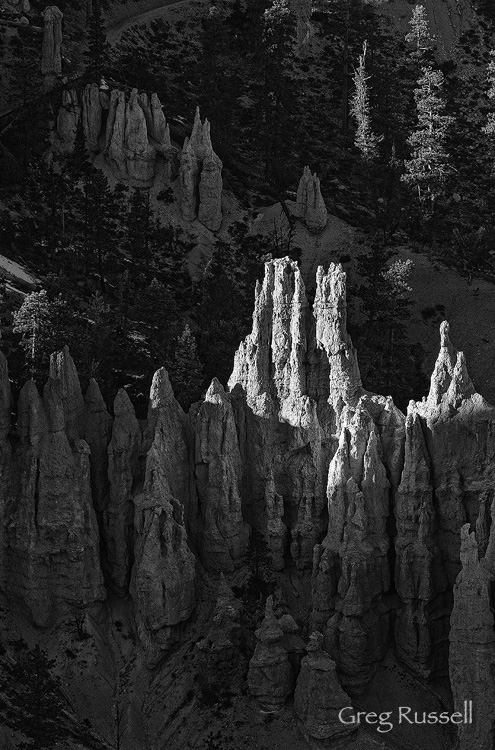

Today is the 105th birthday of Utah’s first national monument: Natural Bridges. The monument protects three large natural bridges, including the world’s second largest, all of which are carved out of beautiful, white, Cedar Mesa Sandstone. Two relatively untamed canyons come together in Natural Bridges, and between the large arcs of stone, Ancestral Puebloan ruins are also protected, standing sentinel over these canyons as they have for hundreds of years. Natural Bridges is out of the way and remote, located in one of the darkest nighttime areas of the United States, earning it the title of the world’s first International Dark Sky Park.

Perhaps it’s an ironic coincidence, but on the birthday of Utah’s first national monument, a group of congressmen–one of whom is from Utah–will begin a hearing in an attempt to undermine the framework of the Antiquities Act. If passed, this body of legislation would require an act of Congress to declare a national monument as well as remove restrictions on land use within national monuments. In Nevada, the Antiquities Act would become null and void (as it is in Wyoming currently). My fear is that in today’s hyperpartisan congress, these changes would make it virtually impossible to use this law as it was intended.

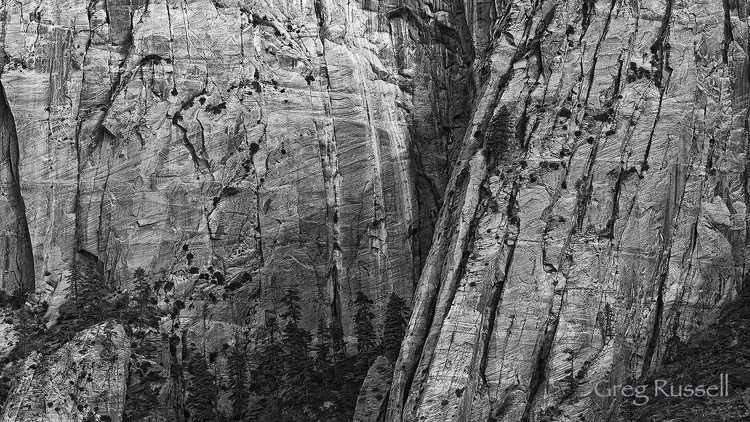

What strikes me even more deeply is the fact that I see the world changing. We are developing land and extracting natural resources at a rate which is simply unsustainable. As a nation, we are slowly but surely abandoning wild places, which is opposite of the notion on which we built our country. Wallace Stegner wrote in his now-famous wilderness letter, “We need wilderness preserved–as much of it as is still left, and as many kinds–because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed. The reminder and reassurance that it is still there is good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it.”

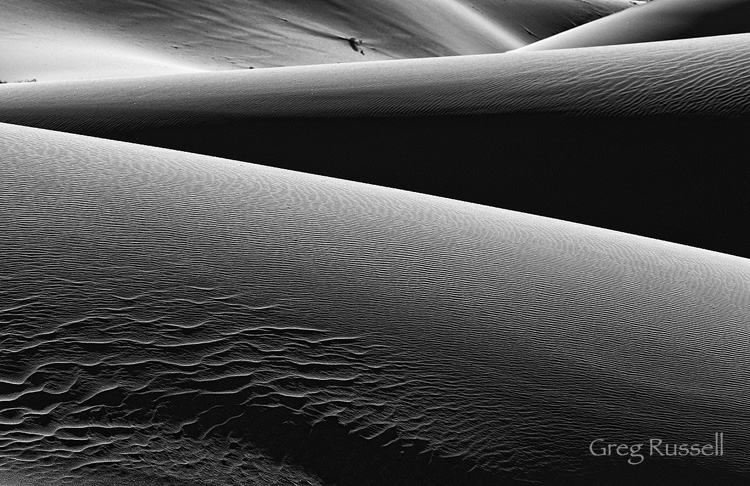

Much has been written on the value inherent in preserving these places and I can’t begin to reiterate all of it here. You can read about clear cuts, pipelines, and mining all day. However, I can’t help but think there’s something deeper happening which we must examine. The material impact of our society on wilderness is obvious, but what about the impact of wilderness on us? Does it no longer move us? Are we no longer in awe of what’s “out there?” Are we simply missing the bigger picture?

What’s the connection to photography? Honestly, I’m still working on this. As landscape photographers, we have the ability to inspire people, to make them want to see places that they might not otherwise see. We have the ability to become an impassioned voice. It’s worth considering, and it beats the alternative. The loss of nature will eventually force us to examine the nature of loss one way or another.

If these mountains die, where will our imaginations wander? If the far mesas are leveled, what will sustain us in our quest to be larger than life? If the high valley is made mundane by self-seekers and careless users, where will we find another landscape so eager to nourish our love? And if the long-time people of this wonderful country are carelessly squandered by Progress, who will guide us to a better world? — John Nichols

When I was a boy I didn’t want to be an astronaut; I wanted to be in the wilderness. I still do.