In addition to its immense, subtle beauty, another overriding theme of the Paria River is mud. The river bed has a high clay content, and if you’ve ever been in clay soil when its even a little wet, you know it can be a disaster–its slick, sticky, and vehicles can get stuck in it in a moment.

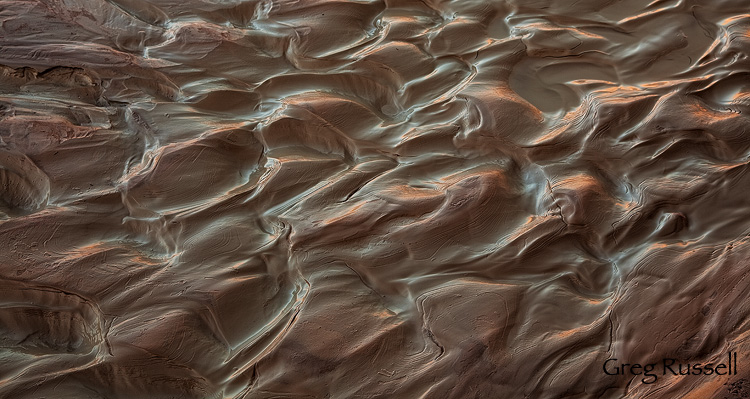

In the spring, runoff from high elevation prevents some mud (by way of keeping from drying enough to reach that sticky, goopy, phase), but its always a factor. What I like about clay is that it always forms beautiful patterns as it begins drying out. This little patch was reflecting the red rock cliffs on the opposite side of the river early in the day.

I also ended up finding a few areas of quicksand, involuntarily, on my hike in the Paria. I felt the area with my hiking pole, and feeling solid, I stepped, only to be swallowed up to my thigh almost instantly. Fortunately, it was easy to pull myself out. People who haven’t dealt with it have a misconception about quicksand. It can’t really suck you into oblivion like childhood cartoons and TV shows lead you to believe. But, as Ed Abbey writes,

Ordinarily it is possible for a man to walk across quicksand, if he keeps moving. But if he stops, funny things begin to happen. The surface of the quicksand, which may look as firm as the wet sand on an ocean beach, begins to liquefy beneath his feet. He finds himself sinking slowly into a jelly-like substance, soft and quivering, which clasps itself around his ankles with the suction power of any vicsous fluid. Pulling out one foot, the other foot necessarily goes down deeper, and if a man waits too long, or cannot reach something solid beyond the quicksand, he may soon find himself trapped. … Unless a man is extremely talented, he cannot work himself [into the quicksand] more than waist-deep. The quicksand will not pull him down. But it will not let him go either. Therefore the conclusion is that while quicksand cannot drown its captive, it could possibly starve him to death. Whatever finally happens, the immediate effects are always interesting.

Finally, the most beautiful effects, in my opinion, happen when the mud begins drying. Because clay expands so much when wet, it cracks in beautiful, wonderfully stochastic patterns. You can find little pockets of dried mud all along the bases of the sandstone walls.

Mud is a major component of the landscape in the Paria, as well as throughout any ephemeral drainage in the southwest. While it can be viewed as a nonphotogenic nuisance, sometimes, its helpful to look at it in a new light.

Most of us, I think, lie somewhere along this continuum. Most people are constrained enough by time (i.e. other commitments in life) that they can’t always wander as much as they’d like. Personally, I do rely on guidebooks and word of mouth to help guide me to pretty locations, but once I’m in the area, I very often will wander, looking for unique compositions. Fortunately, most of these locations are really conducive to letting creativity flow.

Most of us, I think, lie somewhere along this continuum. Most people are constrained enough by time (i.e. other commitments in life) that they can’t always wander as much as they’d like. Personally, I do rely on guidebooks and word of mouth to help guide me to pretty locations, but once I’m in the area, I very often will wander, looking for unique compositions. Fortunately, most of these locations are really conducive to letting creativity flow.