Grizzly bears have been on my mind lately. The mammal that graces California’s state flag was been extirpated from the state almost 120 years ago. However, its legacy remains ubiquitous. Today, we normally associate this holarctic bear species with the northern Rockies–Idaho, Wyoming, Montana. Wilderness travel in these places usually means you carry bear spray in addition to protective measures for food. We occasionally hear of either unwitting or ignorant hikers suddenly learning of their true place in the food chain.

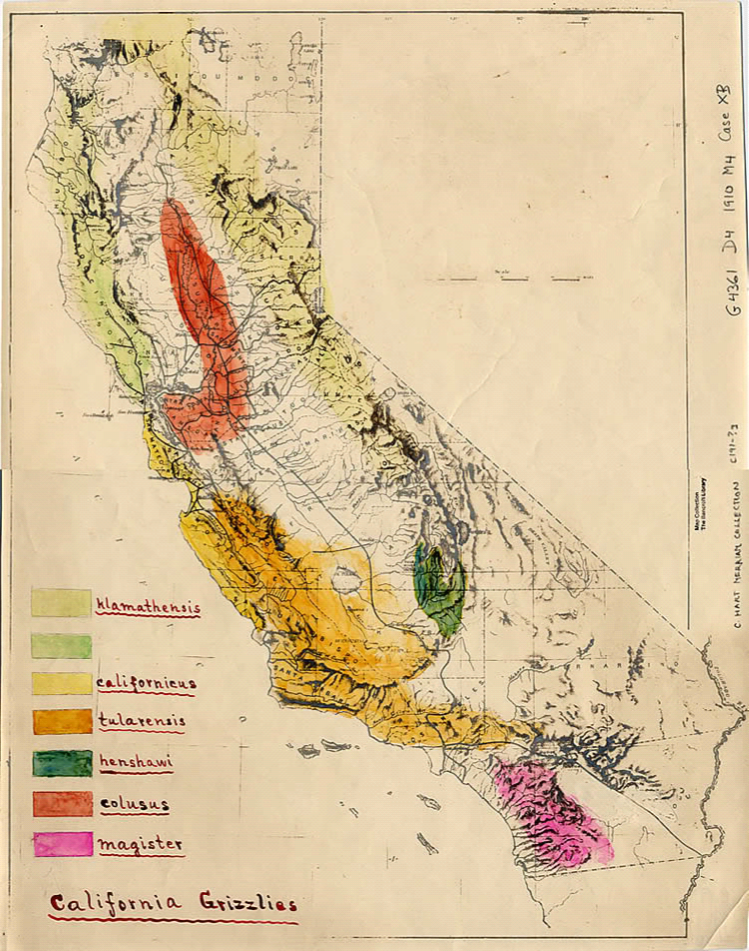

During their reign in California, grizzlies had a surprisingly large range. Biologist C. Hart Merriam initially described at least seven subspecies of Ursus arctos in California, based solely on skull morphology*. In addition to the obvious High Sierra locales, grizzlies were historically common in every major mountain range all the way to the coast. There, they certainly would have feasted on whale carcasses.

One of these subspecies, U. a. magister, called Southern California its home. The Santa Anas, San Jacintos, Cahuilla Mountain, and eastward to the Santa Rosas all were part of magister’s range.

All of these mountain ranges now contain federally designated wilderness areas. Wilderness was conceived in an effort to preserve land in its uninhabited state. This is a very European notion, and one that has received some rightful pushback. The irony is clear: wilderness protects the land and the species that live there, but not the ones deemed too fearsome. Even with our best intentions to conserve, our fear of “the other” pervades. In 1924, California’s grizzly bear was declared officially extinct.

I think about this paradox often when I visit these wilderness areas as part of my Wilderness Project. Recently, I was in the Beauty Mountains, a low lying mountain range on the south edge of the Cahuilla Valley. Looking at the panoramic view around me, I could see every major mountain range in the region. Not far enough from civilization, I heard dogs barking, cars, and at least two mariachi radio stations filling the silence. Still, as the sounds of rural Southern California drifted upward there was room for my imagination to wander to bears.

Laying on a slab of granite, I closed my eyes for a bit. I had been hiking for several hours and wanted to wait until closer to sunset to photograph more. When I shut my eyes, I could picture in my mind’s eye the landscape before me. In it, a grizzly bear lumbered through the Cahuilla Valley, as it might have done 150 years ago. It was flipping rocks and in no hurry at all, working its way toward Million Dollar Spring on its way to higher elevation.

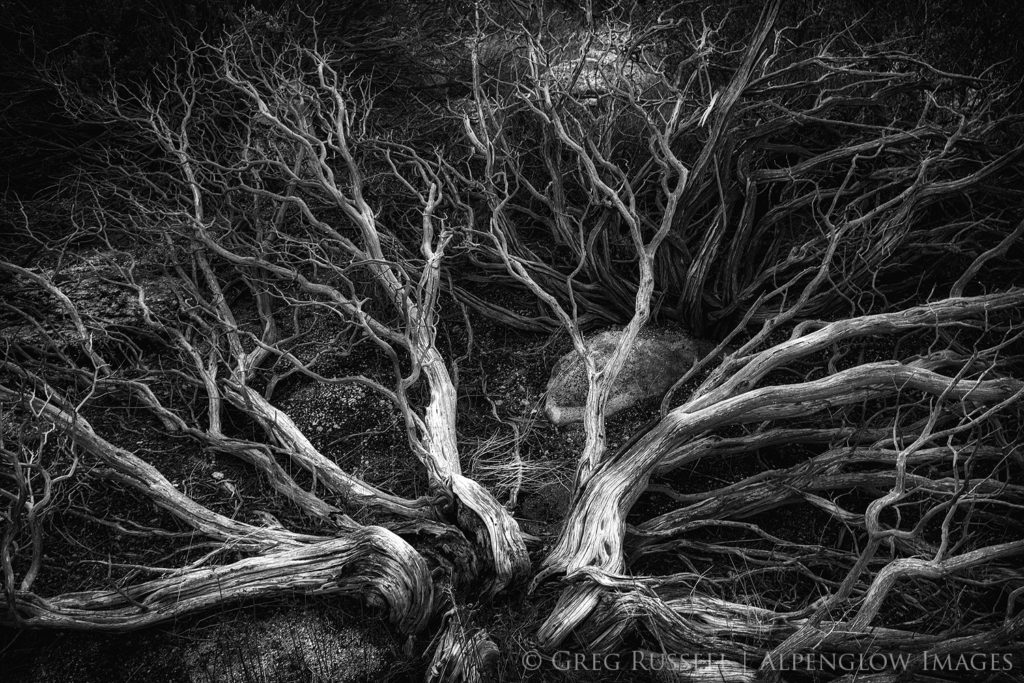

The intent of the Wilderness Project is to document the character of my home range in Southern California. The way I’ve chosen to tell that story is evolving. The images I share with you are partially documentary, but they document these places as I experienced them. I photographed things I have found subjectively significant.

Like grizzlies that once roamed Southern California, my imagination drifts to the stories these landscapes tell. I visualize these wildernesses as a finished story with a deep sense of place. The interconnected map of my home and the finished images are starting to creep through the periphery of my sight line. This gives me brief moments of joy. This project has given me some of my most exhilarating creative moments as a photographer. All this is to say that the project is not drudgery, but a great source of inspiration. Your experience may vary, and it should. For if you visit these places with the sole goal of following in my footsteps, you’re doing it all wrong.

I am heartened by efforts to create habitat bridges and rewild California. Additionally, painting wild nature as our neighbors rather than the other is a long overdue shift in thinking. In my mind, this is a sustainable way of thinking. Grizzlies are the ghosts of California’s wilderness and may never return to Southern California. Can we honor their legacy by telling the story of wilderness today? I can’t go back in time to tell their story, so my goal is to tell the story of the wild nature of my home. One thing I know for sure: these mountains remember grizzly bears.

*Grizzly bears are highly variable in terms of skull morphology, which is not the best indicator of genetic variability. Today, there is one accepted subspecies of California grizzly bear: Ursus arctos californicus.