On Veteran’s Day, my grandfather passed away. He was 92 years old, a WWII veteran and served in two branches of the armed forces during his life (the Marines and Army Air Corps). However, his main career–for nearly 40 years–was as the art teacher in his small town in southeastern Wyoming. A talented watercolorist and sculptor, he drew his inspiration from the natural world around him: wildlife, old barns, and the landscapes of the plains of southern Wyoming.

As a kid, I spent a few weeks each summer visiting my grandparents. We fished almost daily and never missed a baseball game on TV. Indeed, some of my best childhood memories were made with my grandparents, and because he never lost his youthful playfulness, my grandpa was easily my best friend during those summers.

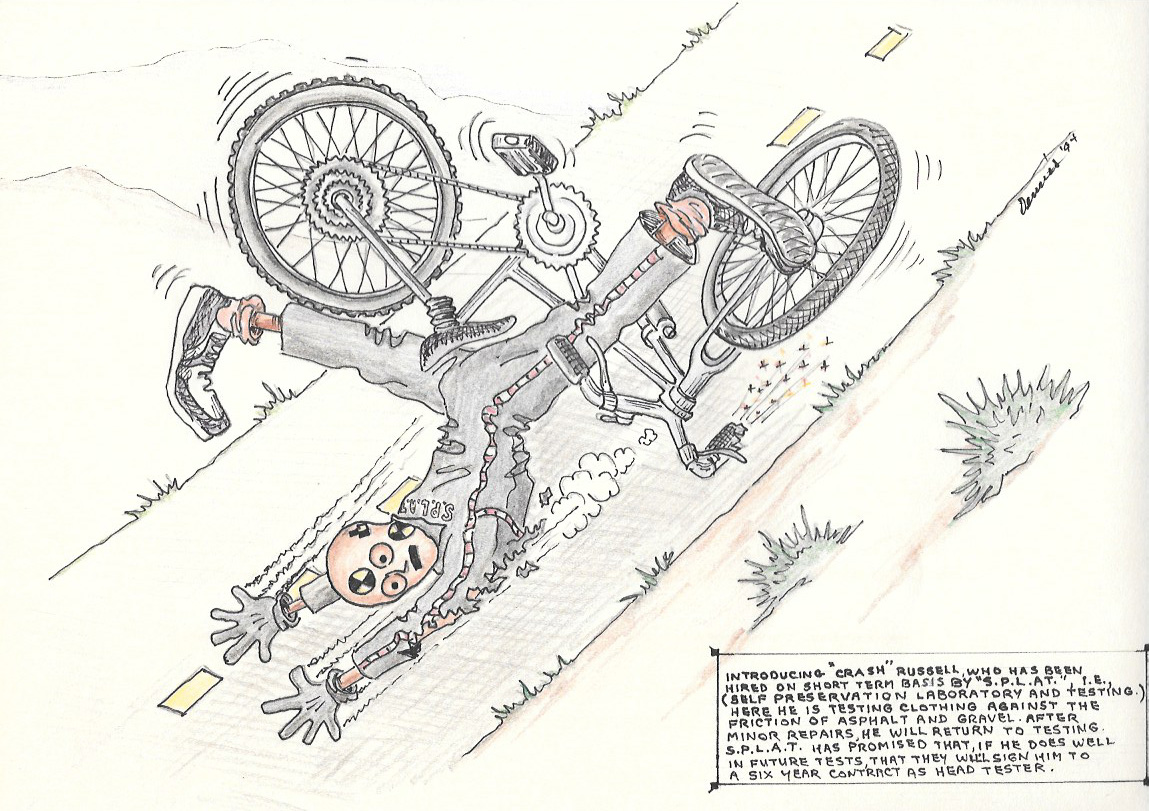

Also, because he was perpetually a kid at heart, he was often caught drawing cartoons of friends–and me–often at our worst. Teasing was something you adapted to quickly in our family because it was relentless.

My Grandpa was incredibly good at poking fun at people with his art. He had a way of making painful things (like bicycle accidents) seem funny.

Of course things change, and I grew older. I attended college at the University of Wyoming and visited my grandparents a few times a semester. After moving to California to attend graduate school, however, my visits became more infrequent. Going back to visit them, the landscape I remembered as a child seemed different: smaller and more compact. Not as wild as I once thought. But the lakes we used to visit to fish still brought happy memories.

Last week I traveled back to Wyoming for my Grandpa’s memorial service. The next day, we spent some time visiting a few of the places that were important to me as a kid. Although the ability to draw seems to have found a genetic endpoint with my Grandpa, it was nice to make a few images with him on my mind.

There’s a certain comfort in knowing someone is there, even if you can’t always see them. Now that he’s gone, there’s definitely a hole that needs filling and he’ll be dearly missed.